Leah Astbury

University of Manchester

2023-12-10

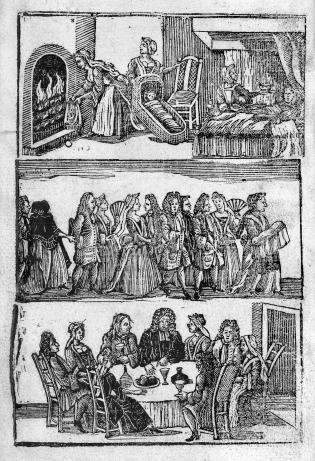

In early modern England babies were not born in hospitals. Women gave birth at home surrounded by female family members and friends, called ‘gossips’ originating from the word ‘godsibb’ or godparent. Babies were almost invariably delivered by female midwives. Better-off women often travelled to their or their husband’s family home to give birth. For such wealthier individuals, when labour began, the woman and her gossips would retreat to a chamber that had been set aside for the birth. For women of all social circles, it was important that the space in which one gave birth was kept dark, warm and that draughts were excluded. Husbands and other male family members were not allowed into the birthing chamber and would retreat elsewhere in the house to wait for the baby to be born.

Many midwives in early modern England were trained through an unofficial system of apprenticeship. After this period, and having an association with one or more senior midwives, they could apply to the Bishop for a license to practice, supported by testimonials from women they had delivered, but many others never felt the need to do so. Research in the last two decades has overturned an assumption that midwives came exclusively from poorer backgrounds, and delivered babies without much training or knowledge in order to support themselves.

Midwives were part of the ‘marketplace’ of medicine and thus might offer advice or medical care during pregnancy in general, as well as in other scenarios. Women convicted of a crime could ‘plead the belly’, meaning claim they were pregnant, to hold off execution, and midwives were often called in as medical experts to definitively say whether or not they were with child. Some midwives also kept casebooks of their medical practice, like Elizabeth Thompson from Kendal in Cumbria, or the records of an unnamed midwife practicing in the early eighteenth century now held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Welcoming a new family member could be a considerable expense for families who had to entertain five or more women and often more people downstairs for the duration of labour as well as pay the midwife. For wealthier households they might also pay for a nurse to attend to the baby, a watch woman to help during the night and a wet nurse to feed the baby. Some of these celebrations can be seen in the frontispiece from Jane Sharp’s The midwives book (1671) which depicts the sociability of labour (first tier), the procession to Church for baptism and churching (second tier) and feasting during childbearing (bottom tier).

Although timings varied, babies were normally baptised a week or so after birth. This was often much sooner if the baby was judged to be unwell because of worries that it would not go to heaven if it had not been baptised or be able to be buried in consecrated ground. Women were expected to take a month to recover from the physical effects of childbirth, a month called called ‘lying in’. After this period, along with her gossips and family members, newly delivered women would travel to church for their ‘Churching’ or ‘Thanksgiving’. This ceremony was called Purification prior to the Reformation. Although women continued to be affected by the bodily and emotional impacts of birthing for months after birth, the ceremony of Churching has often been figured by historians as the ritualistic moment in which a woman returned to her normal life and domestic duties.

Social status and wealth profoundly conditioned the ways in which different women gave birth in the period. When Susan Lay, servant to Francis Beauty, the owner of an alehouse in Essex, gave birth in 1649, her employers hastily removed the child and placed it with a wet nurse in a nearby village. She had to return to work immediately, not least to disguise the fact that Francis, her Master, was the father. Less than six months later she got pregnant again, this time by her employer’s son, William. Heavily pregnant, she was turned out and ‘delivered by the way’, meaning by the side of the road and had to carry the child to a nearby village to receive medical attention.

Stories like Susan’s were not uncommon for domestic servants in early modern England, especially as parishes were keen not to have to shoulder the financial burden of caring for an illegitimate child. Midwives’ oaths almost invariably included a promise to extract the name of the father of a child if the mother was unmarried so as to ensure the parish did not have to pay for its upkeep. When Anne, the Countess of Macclesfield, had an affair and gave birth to a child that was not her husband’s, she rented an apartment in Holborn in London, and wore a mask so the nurse and midwife would not recognise her. Although having a child out of wedlock was unequivocally condemned by religious and legal authorities in the period, Anne’s experience suggests that money and status could shield some women from the worst bits of unwed motherhood. However, Anne too suffered consequences. In 1698 her husband, Charles Gerard, petitioned parliament to have her and her ‘spurious issue’ disinherited, and divorced her in the process.

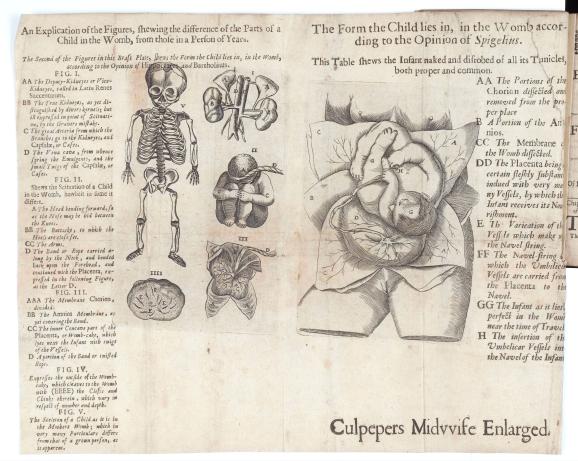

Early modern people found out how to make babies from a number of different sources. Childbearing manuals were amongst early titles published in the wake of the invention of the printing press but there was a boom in these books printed from the 1650s. Male authors, usually physicians, quoted, adapted and co-opted older manuscript Latin texts, to construct new accounts of the correct way to bear children. The first English midwifery guide, The byrth of mankynde (1540) was a translation from a German text; the next, Child-birth or, The happy deliuerie of vvomen (1612) was translated from French. Perhaps the most famous and popular childbirth guide written by an English author was by Nicholas Culpeper, also a herbalist and astrologer, called A directory for midvvives was published in 1651.

As the seventeenth century progressed, more and more people were literate and books became cheaper. As a teenager in rural Somerset in 1700, John Cannon described in his diary how he bought a second-hand copy of As the seventeenth century progressed, more and more people were literate and books became cheaper. As a teenager in rural Somerset in 1700, John Cannon described in his diary how he bought a second-hand copy of Aristoteles Master-piece (1684) the best-selling popular childbearing and sex guide of the period, for only a shilling. He used it to find out about the ‘secretes of nature, especially of the female sex’ and as masturbatory material. He subsequently acquired a copy of Culpeper’s A directory for midvvives for the same nefarious purposes, but the book was promptly confiscated by his mother. For those who never read or saw these midwifery guides, information about sex and childbirth might be shared by orally, in ballads or drinking songs.

Because much knowledge about sex and childbirth may have been transmitted by word of mouth and not recorded, historians have only a partial account both of what early modern people knew about procreation and the practices surrounding it. As well as reading conduct manuals that described domestic activities and duties, medical guides and ballads, a historian might occasionally be able to find information about childbirth in the diaries and letters that some early modern people wrote. Men and women who were literate often recorded details about the births of new family members in their papers. Recipe books that many more elite families kept contain many remedies to ease the discomfort of pregnancy, hasten birth, stop flux or bleeding after birth and to improve newborn health, indicating considerable care and expense was taken at home to ensure childbirth was as safe as possible.

Image sources

Jane Sharp, The compleat midwife’s companion (1724). Wellcome Collection.

Nicholas Culpeper, A directory for midwives (1671). Wellcome Collection.

Further readings

Astbury, Leah, “Being Well, Looking Ill: Childbirth and the Return to Health in Seventeenth-century England.” Social History of Medicine 30, no. 3 (2017): 500-519.

Cressy, David, “Purification, Thanksgiving and the Churching of Women in Post-Reformation England”, Past & Present 141(1993): 106-146.

Evenden, Doreen, The Midwives of Seventeenth-century London. (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Fissell, Mary E., Vernacular Bodies: The Politics of Reproduction in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Gowing, Laura, Common Bodies: Women, Touch and Power in Seventeenth-century England (New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press, 2003).

—, ‘The Haunting of Susan Lay: Servants and Mistresses in Seventeenth-Century England’, Gender & History 14, no. 2 (2002): 183-201.

McClive, Cathy, “The hidden truths of the belly: the uncertainties of pregnancy in early modern Europe.” Social History of Medicine 15, no. 2 (2002): 209-227.

Pollock, Linda A., “Childbearing and female bonding in early modern England.” Social History 22, no. 3 (1997): 286-306.

Whiteley, Rebecca, Birth Figures. Early Modern Prints and the Pregnant Body (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2023).

Wilson, Adrian, The Making of Man-Midwifery: Childbirth in England, 1660-1770 (London: UCL Press and Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).